By Jim Hingst

“It’s unwise to pay too

much, but it’s worse to pay too little. When you pay too much, you lose a

little money – that’s all. When you pay too little, you sometimes lose everything,

because the thing you bought was incapable of doing the thing it was bought to

do. The common law of business balance prohibits paying a little and getting a

lot – it can’t be done. If you deal with the lowest bidder, it is well to add

something for the risk you run, and if you do that you will have enough to pay

for something better.”

John Ruskin

Setting prices for your work is a

balancing game. If you price jobs too low, you won’t make enough profit to expand

your business. Priced too high and you will price yourself out of work. In a

worse-case scenario, you could go out of business.

In many cases, shops establish their

prices so that they are in line with the competition. Based on information from

their sales people and customers, they compile pricing information on the

competition. For example, using data from the field you can assess what other

shops are charging per square foot for digital printing.

You can encounter several problems, if

you set pricing based on the competitor’s prices. The first is that you are

pricing your work as if you are selling a commodity. You should not position

your shop as an apples-to-apples business or the low-cost producer. Instead,

you should emphasize your unique

selling proposition as a specialty house that designs, manufactures and

installs corporate identity programs. Your value-added is in helping other

businesses visually communicate so they can gain larger shares within their markets.

Problems

with Underpricing. When was the last time that you increased

your pricing during a negotiation? It NEVER happens! Low balling your

price gives you no bargaining room when faced with the customer who wants to

haggle. When you start high, you can easily come down in price – not the other

way around.

If you

get what you pay for, don’t you get more value when you pay more? Maybe not.

Pricing products at a premium, however, implies that you provide higher quality

products; your services are better; and you have the financial resources to

warranty your products in the event of a problem.

Conversely,

underpricing your products and services diminishes your brand. Low-ball pricing

suggests that your products are inferior. Selling on price is a mistake that

both novice and experienced salespeople make. It sends the wrong message to the

buyer.

Overpricing. Overpricing can

create as many prices for a business as underpricing. An abrupt increase in

pricing can create distress and resentment among customers. Consistency in

pricing, on the other hand, fosters trust.

The Difference Between Cost and Price. Some shop

owners underprice jobs because they have a limited understanding of how to cost a

project. What’s more, many also don’t understand the difference between cost

and price.

Cost. Costing a job involves estimating

your cost of goods sold and apportioning an appropriate amount of your overhead

to it. Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) calculates the direct costs that go

into manufacturing a job. These direct costs include raw materials, direct

labor and any other direct expenses. Overhead comprises your fixed shop and

administrative expenses.

Cost of Goods Sold and Cost of Sales are often used

interchangeably. For a manufacturing business, such as a sign shop or a digital

printer, Cost of Goods Sold is generally used. Cost of Sales, on the other

hand, is a term typically used for a retail business.

Overhead. In estimating jobs, you

need to allocate a portion of the overhead. In a job shop, such as a screen printer or

sign company, overhead includes your expenses. It does not include direct

expenses, such as raw materials, labor charges and other direct costs, used in

the manufacturing of products.

To allocate or charge a portion of indirect expenses to jobs,

overhead is often used to calculate an hourly shop rate, which may also be

referred to as a burdened shop rate.

These expenses are usually grouped into broad categories,

including selling, general and administrative expenses, referred to as SGA. In

larger companies, manufacturing overhead used in product production is

considered as a direct expense.

In a small sign company, segregating manufacturing overhead from

other shop expenses is as fruitful as trying to determine how many angels can

dance on the head of a pin. For this reason, it is more expedient just to lump

all indirect expenses under the umbrella of “shop and administrative expense”.

In the end, your costing system needs to cover all of your direct

costs and indirect costs in the production of your products. What job cost does

not cover is profit.

Pricing. In setting your pricing, you need to cover

all of your direct costs as well as a fair share of your shop’s overhead. On

top of that, your company needs to make a profit.

The business is a separate entity from anyone who works there.

Anyone who has invested in the business deserves a return on their investment. The

business also needs profit to expand.

Running a profitable shop is also important, so that at some point

you can sell the business and enjoy a comfortable retirement. It is

disconcerting to hear a shop owner state that they intend to work until they

die. Many of these businesses are just covering their costs. Why would any

investor buy a business that runs on a break-even basis?

You can improve your bottom line in a

number of ways. These include cutting shop and administrative costs, reducing

scrap rate and improving shop productivity. All of these activities work.

Another effective strategy which can improve profit that produces results but

causes anguish among salespeople is to raise your prices.

Pricing Strategies. Calculating the cost of a

product isn’t that difficult. What most people have a problem with is

determining where to set your price. Sadly, no standard pricing formula is

available. Some of these pricing strategies, which include Break-Even Pricing,

Market-Based Pricing, Cost-Plus Pricing and Value-Added Pricing are covered in

this article.

Break-Even Pricing. Some shops price jobs just to cover their

material costs and labor with a little extra so they can pay their bills. While

many of shop owners are pleased to break even and make a living wage, the

business isn’t making a profit. Just as you need to be paid for your hard work,

the business is an entity separate from its owners and needs to be paid.

While break-even pricing is not a recommended

strategy, some exceptions to this rule make sense, especially for a new

business with significant debt. Taking on major accounts on a break-even basis

can help to keep the lights on. These “overhead jobs” can cover all of your

direct expenses and a significant portion of your shop and administrative

expenses.

Market-Based Pricing. Basing your prices on the competitor’s

prices may not account for the differences in your business. Your overhead and

material costs may differ from other shops. You need to estimate your costs and

profit margins based on your operation, not on how another shop runs his

business.

You should set your pricing at whatever

the market can bear. To determine how your pricing stacks up with the

competition, incrementally increase your prices until you start to lose

business.

The problem is competing with competitors

who have a limited understanding of estimating. This is one reason so many of

these companies go out of business within the first couple of years. What’s worse,

is that these shops screw up the market pricing for everyone else.

It is difficult to contend with

ridiculously low pricing. When dealing with a new business, you can frame the

conversation by comparing your long history and financial stability with their

inexperience.

Blatantly slamming a competitor is generally

not well-received and usually backfires on you. Instead you can describe your

company by saying, “we are not a fly-by-night organization that just opened its doors yesterday. We have a long history of handling major graphics programs.”

Then provide examples. “We also have the financial stability to handle any problems

in the unlikely event of a graphics failure.”

Another

strategy in dealing with a competitive challenge is to offer your prospect with

two or three options, each priced at different levels. Other than price, each

graphics package could feature different raw materials. Instead of selling on

price, each package would offer its own advantages. Presenting a prospect with

a choice between these options often facilitates the closing process.

Cost-Plus Pricing. A number of

my employers in the graphics and construction fields priced their jobs in this

manner. These companies would cover all of their raw material costs as well as

other direct outside costs and add in a fully-loaded cost for labor, which

accounts for an apportioned amount of their overhead. To that cost, the shop

would tack on a percentage for profit.

At some shops, owners would mark up jobs at a fixed rate. The

simplicity of cost-plus pricing using a fixed rate makes perfect sense. The

problem is that it does not allow you any wiggle room to negotiate in

competitive situations. It also does not account for the value that you provide

customers, for producing an outstanding product that differentiates you

business from your competitors.

Cost-plus pricing using a graduated scale makes more sense. In

this system the salesperson marks up to job based on his or her assessment of

what would close the deal. In this system, a percentage would go to the company

and the remainder would be paid to the straight-commission salesperson.

Using a graduated scale, the salesperson could mark up the job to

account for bids from other shops. As an

example, if the rep decided to sell the job at a 40% markup, they would earn

20% in commission. On the other hand, selling a job at 25%, the rep would only

earn 10% on the job, while the shop took 15%.

This system provides reps with the flexibility to adjust prices

based on competitive pressures. It also provides reps with an incentive to sell

at a higher markup.

Value-Added Pricing. Optimizing prices requires you to sell

your shop’s value-added benefits rather than pricing based on a cost-plus

basis.

In the graphics business, value-added

means that you are positioning yourself as a business consultant, selling

solutions to a prospect’s problems. You are fulfilling unmet needs that the

competitors are not satisfying.

When you price according to what

competitors are doing, you are simply reacting. You raise your prices when a

competitor raises theirs. You lower your prices when they lower theirs. Does

that make pricing sense? With a value-added pricing strategy, the additional

value that you provide customers should justify higher pricing.

When you price your jobs, you should

emphasize the value-added features and benefits that your company provides.

Your presentation should include:

• Design. An explanation of how your

design satisfies the prospect’s marketing and corporate identity objectives;

• Materials. A description of the

raw materials used in the job. Quality materials,

such as the type of vinyl films used, ensure the longest service life of the

graphics. Conversely, use of cheaper materials results in failures.

In their presentations, the 3M Company has

effectively emphasized the problems which can result when using substandard

films. In selling fleet graphics, you can provide photographs of vinyl films

channeling in the valleys of corrugation, cracking, peeling and tenting around

rivet heads.

• Manufacturing. How a job is

engineered and manufactured is a major factor in the service life of outdoor

graphics. Your sales presentation should emphasize any differences in product

construction, raw materials used and manufacturing processes.

• Installation. As part of a graphics

package, you can differentiate your proposal by including vinyl application. You

should emphasize that work is performed by a certified professional decal

installer, who has been formally trained and carries liability insurance. Professional

application provides the customer with the peace of mind that the work is done

right and is warrantied.

• Service. After-the-sale service

covers any corrective action and customer support during the service life of

the product. An outstanding service package provides the prospect with a reason

to pay more for your products.

Once you have converted prospects into

customers, after-the-sale service is the cornerstone to protecting your

business base. A reputation for reliable after-the-sales support helps build

strong customer relationships and a strong brand. In most cases, unsolicited

word-of-mouth endorsements are much more effective than any advertising

campaign you might devise.

Financial security. If your shop is well-established and

well-funded you can provide customers with the peace-of-mind that your business

has the financial stability to warranty its work in the event of a product

failure. In selling, you can use your experience and the financial strength of

your shop as a wedge to drive between the prospect and the incumbent graphics

provider.

When You Should Increase Prices. Do you have more work than

you can handle? If no one has complained that your prices are too high, your

prices are probably too low. Getting all

of the jobs that you bid on is another indication that your prices are much

lower than your competitors. You should increase your prices until you start to

get some push back.

If your business is growing, your shop

and administrative expenses will also grow. To expand, you need to set your

pricing so you not only cover all of your expenses, but you have enough profits

to hire new employees, buy additional equipment, and upgrade and expand your

facilities. If your business is not generating enough profit to finance this

growth, you need to raise your prices.

Profitability Metrics. You can

assess the profitability of your shop using different metrics or measurements.

You can use these measurements as key performance indicators (KPIs) to gauge the progress of your business. There are three

profitability metrics that you need to track:

• Gross Margin Ratio;

• Operating Margin; and

• Net Profit Margin.

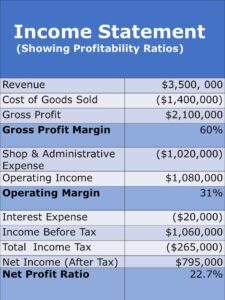

Here’s

how Gross Profit Margin, Operating Margin and Net Profit Ratio compare in an

Income Statement:

Gross Margin Ratio is

important for many graphics shops. After you subtract Cost of Goods Sold (often

called Cost of Sales), the difference is what you have left to pay for your

Shop and Administrative Expenses. Here is the formula:

(Total Revenue – Cost

of Goods Sold) ÷ Total Revenue = Gross

Margin Ratio

Example

($3.5 million in sales

– $1,400,000 Cost of Goods Sold) ÷ $3.5 million = 2,100,000/$3,500,000 =.6

or 60%

When I worked for a large

screen printer, the shop had an objective of operating at a Gross Margin Ratio

of 60%. The inverse of that ratio is a cost of sales of 40%.

Here’s why Gross Margin is

important. With annual sales of $3.5 million, it meant that $2.1 million was

available to pay for an overhead of $1 million. The remainder was left to cover

interest, taxes and depreciation. Anything left was net profit.

Each business is different.

Smaller sign shops typically should operate at a Gross Margin Ratio of 80% or a

cost of sales of 20%.

Changes in Gross Margin

Ratio are a barometer which can measure the overall health of your business. These

changes can alert you to problems. If

your Cost of Goods Sold increases while sales stagnate or decline, the change probability

indicates a problem, resulting from:

• Poor purchasing practices;

• Failure to adjust estimating standards to account

for inflation;

• Estimating mistakes;

• Poor production planning and management;

• Inadequate sales and marketing strategy;

• Lack of sales management and training;

• Unforeseen competitive pressure; and

• Failure to hold sales personnel accountable.

Operating Margin. In addition to gross profit

margin and net margin, many analysts will look at operating margin as an

indication of your shop’s overall financial health. Operating margin is based

on profit before paying interest and taxes. It is not the same thing as EBITDA,

which also factors in depreciation and amortization.

If you are looking to secure

additional financing from your bank to expand your business, operating margin

is an important metric that the bank looks at. As a rule of thumb, a healthy operating margin above

20% signals to lenders your ability to pay back loans and that you have enough

money to pay your taxes and take care of your other financial obligations.

In computing operating margin,

the first step is to calculate your operating income:

Revenue – (COGS + Shop &

Administrative Expense) = Operating Income

Example:

$3,500,000 – ($1,400,000 + $1,020,000) =

$1,080,000

To

determine your operating margin, divide your operating margin by your revenue:

Operating Income ÷ Revenue= Operating Margin

Example:

$1,080,000 ÷ $3,500,000 = .31 or an Operating Margin

of 31%

Net Profit Margin. Gross profit margin ratio

isn’t the only benchmark for rating the performance of a shop. At the end of

the day, the effectiveness of a business comes down to the net profit margin or

bottom-line profitability.

To

calculate net profit margin, subtract all of your expenses, which includes taxes and interest expense, as well as cost of goods sold and shop and

administrative expenses from your revenues or sales.

To

calculate your Net Profit Ratio use the following formula:

Net Profit (after Taxes) ÷ Revenue = Net

Profit Ratio

Example:

$795,000 ÷ $3,500,000 =

22.7%

To improve the profitability of your shop, you can

take the following steps:

• Review and adjust your estimating standards and

procedures;

• Increase your profit margins;

• Reevaluate contracts with your vendors to control raw

materials costs;

• Reduce your shop and administrative expenses; and

• Examine and correct your production performance and

procedures.

Conclusion.

When you are presenting pricing for a

graphics program, NEVER present prices for the individual components.

This gives your competitors an opportunity to pick apart your pricing and

present counter bids on the components. When making a proposal, present pricing

for the whole package including installation.

To effectively justify your

pricing, you must first understand the prospect’s business objectives as well

as what is important to him personally.

This is why needs analysis is such a critical step in the sales process.

The next step is to demonstrate how your program delivers value by satisfying

those objectives and needs.

Positioning Your Business. Price your programs to reflect your shop’s

positioning in your market. If you are the best graphics designer in your area,

you deserve to be the highest priced shop. If your shop has produced graphics,

which have won design awards, your marketing should publicize your standing in

the industry.

If you are positioning your shop as an

industry leader and expect to be paid accordingly, make sure that you look like

an industry leader. You have probably heard the saying that if you want to make

a million dollars, dress like a million dollars. This is especially true in selling graphics

packages.

As a graphics provider, you are in an

appearance-based business. You are selling corporate identity programs to make

other businesses look better than their rivals. In positioning your shop as the

undisputed best in visual communications, you need to play the part of an

industry consultant. The image that you project in all of your communications

is essential in commanding higher prices.

As you build your brand and your reputation,

you also build demand for your services. When you are in demand, you can demand

higher prices.

Good Luck Selling!

© 2021 Jim Hingst, All Rights Reserved